BLOG VIEW: The Ginnie Mae Early Buyout program does not need to be modified – it needs to be eliminated.

Ginnie Mae should make principal and interest payments on delinquent loans. Servicer advances were designed to incentivize the servicer to process delinquent loans quickly and efficiently – yet a higher level of non-performing loans result in emergency measures to finance growing delinquent principal and interest advances.

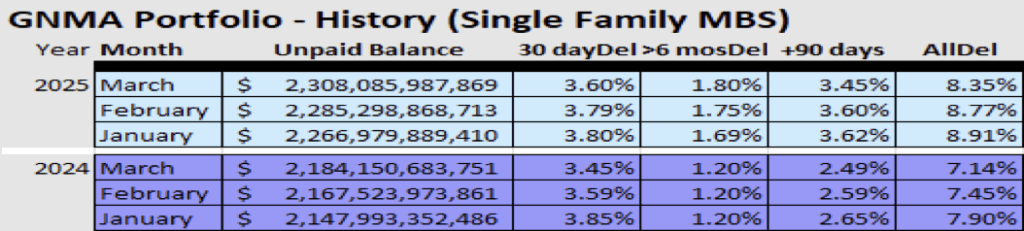

As overall Ginnie Mae delinquency levels have increased about 15% over the last 12 months let us reevaluate the necessity (and risks) of servicers making delinquent advances for Ginnie Mae securities.

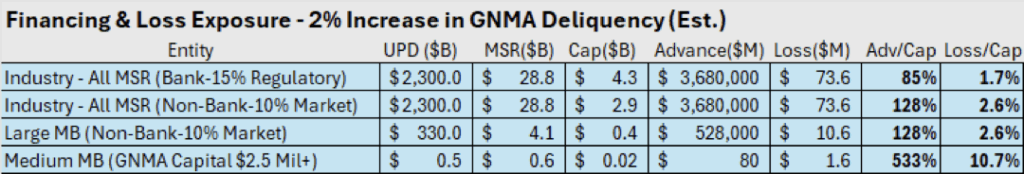

For well capitalized Ginnie Mae servicers, advances as a percentage of capital* are manageable, but hardly insignificant, as special purpose vehicle financing may be required.

Advances are ~100% of capital with just a 2% increase in delinquency. For medium sized servicers ($50 billion UPB in the estimates), it is a business ending scenario with advances many times capital and financing losses (if they can get credit) potentially wiping out profits.

The ability to finance and absorb earnings hits due to financing or earnings losses on servicer advances is most damaging to medium sized originators. Assuming an increase of 2% in overall delinquencies, here is an estimate of the advance/MSR equity and loss/income ratios for 1) the entire industry, 2) a large Ginnie Mae servicer, and 3) a medium sized servicer:

Periods of financial stress resulted in third party financing solutions such as servicing advance facilities (SARTs) that were created in the Great Recession to fund growing advance liabilities due to a significant increase in delinquent loans. Fortunately, lower than expected acceptance of allowed borrower COVID forbearance sidestepped a big funding problem.

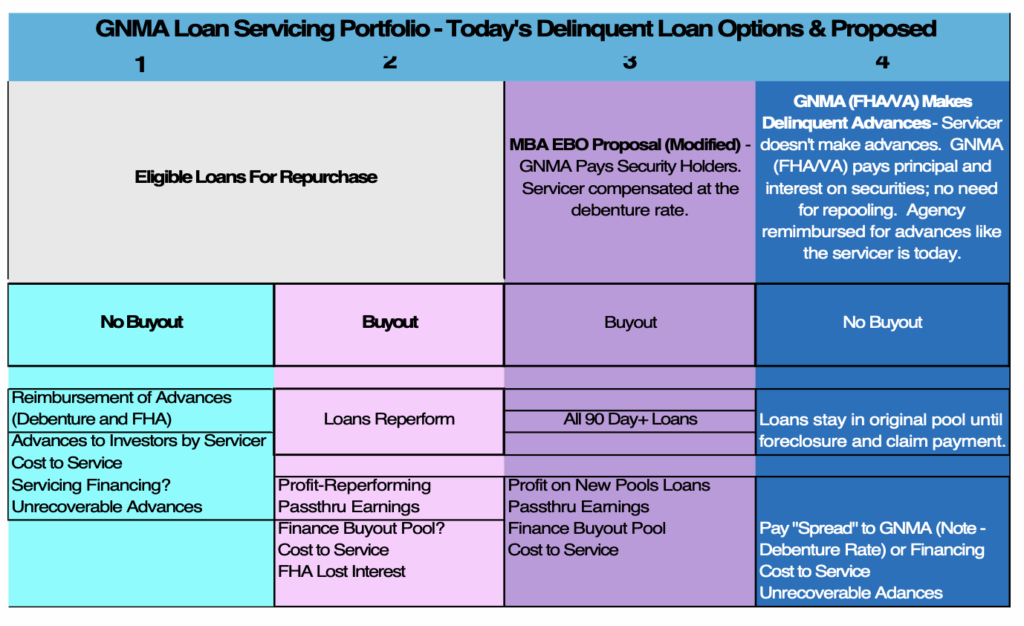

A summary matrix of the convoluted servicer revenue and expenses model existing today for Ginnie Mae delinquent loans (in existing pools or “buying out” loans) along with the MBA proposal (modified), and eliminating servicer advances is as follows:

Looking at the complicated security pooling system of today (numbers 1 and 2 above) and its associated advance rules and funding problems, the common-sense solution is (and always has been) Ginnie Mae (FHA/VA) making delinquent advances. How would servicers, investors, and the agency be impacted?

Would elimination of advances result in servicer inefficiency? The agency holds the servicer’s license to do business, Ginnie Mae monitors the performance of the issuers/servicers, able to require additional capital, improved operational measures, and/or in worst case transfer the MSR portfolio to another licensed entity. The issuer has many reasons to continue to service troubled loans in an efficient manner:

- The cost of servicing multi-month delinquent loans rises exponentially from 1 month late through foreclosure.

- The servicer will still have to pay the cost of financing or the spread between the security rate on the pool and the debenture rate as posted by Ginnie Mae.

- Advances will be charged to the servicer if deemed non-recoverable by Ginnie Mae.

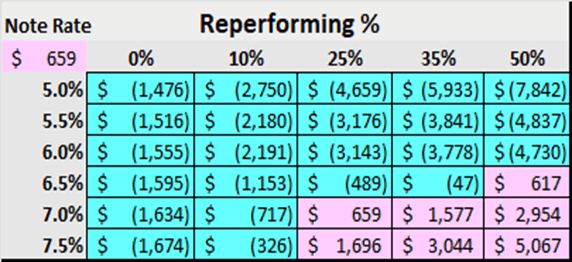

Would servicers be happy about losing buyout profits? No, it has been a key profit center for some larger players. Is it a reliable profit center or are servicers kidding themselves? Buyout profits are only realized on reperforming delinquent loans that are subsequently “repooled” at par, the outcome of a modified loan becoming current and current mortgage rates well below the current borrower note rate. Look at the following servicer “advance” economics of buying-out delinquent loans.

Servicers profit from a buyout, on “in the money” loans versus continuing to service and make security advances only on higher note rate reperforming loans. I was always amazed at the assumption that all 90-day delinquent loans that are “in the money” should be purchased from an existing pool. The EBO sale profits need to be significant, and you should have high confidence the borrower will reinstate payments. Of course, with a buyout you are funding the entire loan not just the lost payments; it’s the playground of the larger mortgage banker who doesn’t calculate the funding costs correctly.

How would investors react to an Agency advance policy? The investor remains financier until a foreclosure/claim results in loan prepayment. Principal and Interest on delinquent loans continues to be paid to investors and buyouts would not be necessary with pool prepayments (from losses) deferred as long as possible. Evaluating the impact of issuer buyouts would be unnecessary. Reperforming pools would not be issued.

Operationally, can Ginnie Mae handle a no advance model? Advances, reimbursement of advances (and taxes), collecting financing or debenture interest from the servicer remains the same, with FHA and VA collecting reimbursements (from themselves) instead of paying the servicer. The servicer’s investor accounting department handles the monthly reporting so Ginnie Mae should be fine with their smallish staff. The operations and accounting would be like Servicing Advance receivable transactions (SART). Ginnie Mae refunds advances made by the servicers now, it is a timing issue for the agency insurers.

The EBO and SART markets are not necessary. EBOs were designed to offset advance financing costs while advance receivables filled a need created by Ginnie Mae servicing advance requirements. The agency could charge the servicer the cost of funding the advances it provides (same as a SART). However most important, the large burden of funding security advances, overall significant and disastrous when delinquencies rise, would be lifted.

Nick Krsnich is managing member of JMN Investment Management, a financial industry portfolio management and consulting firm. He was formerly the chief investment officer of Countrywide Financial Corp. and board member of Counrtywide Bank.

*Under Basel III (implemented in the U.S. via the capital rules issued by federal bank regulators), MSRs are treated conservatively due to their volatility and valuation risk. Key Capital Treatment Rules:

Deduction Threshold for Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1):

- MSRs are part of the “threshold deduction” items alongside deferred tax assets (DTAs) and significant investments of unconsolidated financial institutions.

- Banks can include MSRs in CET1 only up to 10% of CET1 capital (individually).

- The aggregate cap for all threshold items is 15% of CET1.

- Excess MSRs beyond these thresholds must be deducted from CET1.

- Implication: For banks, carrying too many MSRs reduces their regulatory capital ratio unless they are sold off or hedged.

Photo: Blogging Guide